Critical questions ops leaders need to ask when building Agents

You don't need to be an engineer to design agents but you do need to know when they start, how they works, how to retry, and how to test safely. Read: "Everything Starts Out Looking Like a Toy" #286

Hi, I’m Greg 👋! I write weekly product essays, including system “handshakes”, the expectations for workflow, and the jobs to be done for data. What is Data Operations? was the first post in the series.

This week’s toy: an archive of fictional brands. Some might say that learning about Cyberdyne Systems is not needed for cultural literacy, but this site will help you when you’re not sure if a brand is real or not and you don’t want to depend on your local AI bot.

Edition 286 of this newsletter is here - it’s January 6, 2026.

Thanks for reading! Let me know if there’s a topic you’d like me to cover.

The Big Idea

A short long-form essay about data things

⚙️ Critical questions ops leaders need to ask when building Agents

I just submitted my first PR for an Agent, and learned a lot in the process. The biggest change? My mental model for building Agents going forward.

My assumption going in was that I’d be able to write some code, specify some decision points, and end up with a production agent. Silly me, and the best way to enlighten yourself to that gap is to go build and write up your learnings after you’ve gone through the process.

Agents, like other code, often reach production carrying unexamined assumptions about authority, cost, failure, and trust. If your team is building agents, your job as an Ops Leader isn’t just to understand the “jobs to be done” or only to read the code if you’re a technical lead.

Your job is to ask the questions that surface operational risk in Agents before that risk shows up in an incident. The side benefit? You’re anticipating failure points before they happen.

What is this Agent’s job?

Begin with the end in mind. After this Agent wakes up and does its job, what should happen?

A good answer to this question looks a lot like a quality user story:

This code triggers [how often, on an event] and [does a series of specific actions], resulting in a decision to [action verb] a record with [data]. If [boundary condition], the Agent shuts down.

For example:

“This code checks every day for a record that has no value in a specific custom field and based on another field sets a classification value in that target field. If the result is inconclusive or the agent takes more than 30 seconds to run, the record is marked as “needs remediation” and the code is stopped.”

If your Agent has a clear remit, it’s a lot easier to confirm it got the job done.

Finding the safe high-leverage task to complete

Agents can do almost ... anything. So it’s a good idea to isolate them from high-tension interaction with the customer until you know the broad spectrum of outcomes.

Customer-facing triage and recommendation is a great place to start, because the actions are reversible and fixable.

Examples:

classifying inbound support requests

recommending escalations

flagging account risk

suggesting follow-ups

normalizing messy customer inputs

These tasks work well because they share four properties:

High volume (real leverage)

Low blast radius per decision

Human override is natural

Outcomes are easy to observe

When you give these tasks to an agent, you’re succeeding when the tasks get doen without human interaction and your team can focus on higher value tasks.

A successful agent is one you would expect to get the job done more often and effectively than a human (that also proves it).

How do we isolate and control the authority of this agent?

What could possibly go wrong? That’s the question you need to be asking when you start using an Agent.

Start by identifying whether you are working with reversible or non-reversible changes. Flipping a bit on a record might not cause a problem. Deleting a record and causing a cascading delete of other records is a much bigger potential problem.

You can control a lot of what could go wrong by testing carefully and by quality checking your code. Adding unique credentials for that agent makes it possible to remove access and to see actions in a log.

What permissions does the agent need to finish its job? Don’t delegate more than necessary. If you can get the job done with read, you don’t need write.

What makes the agent start and stop?

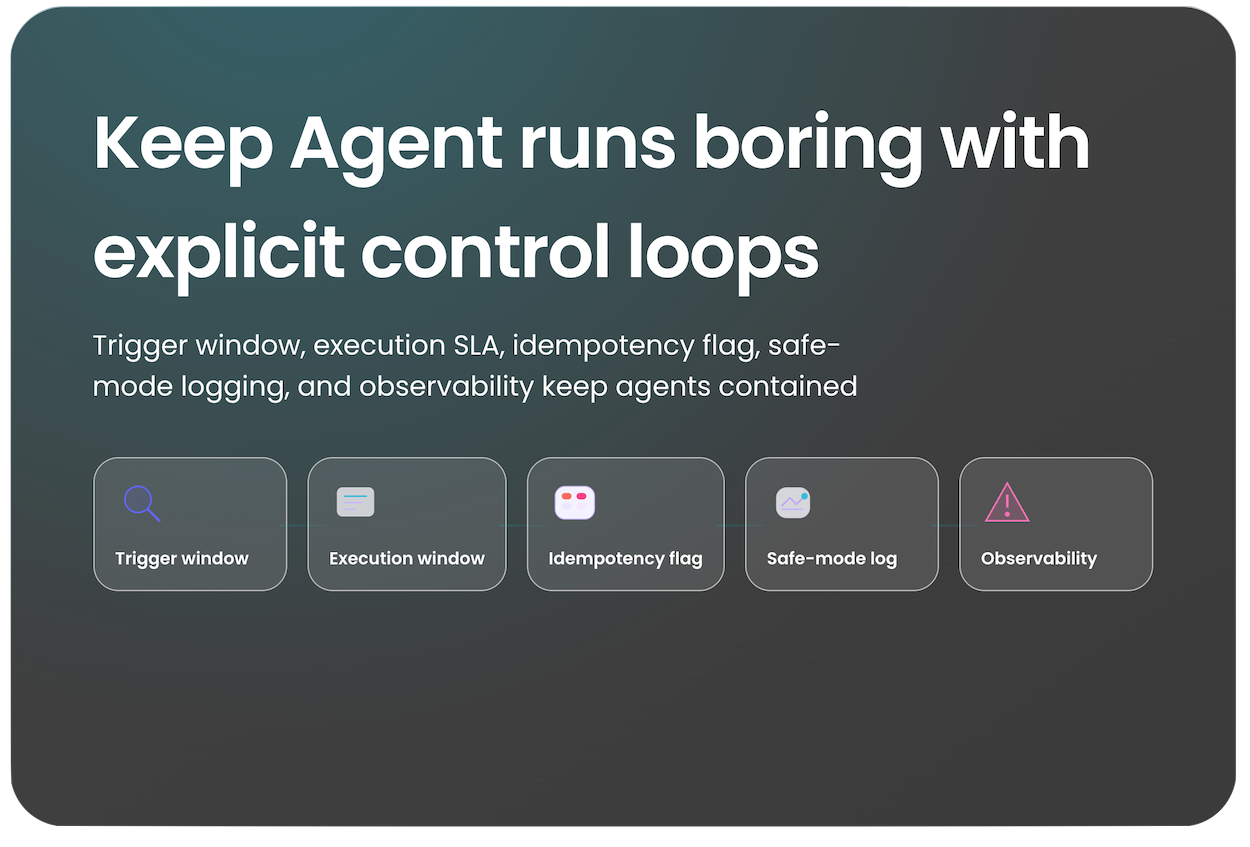

If you don’t know what makes your agent start and stop, don’t deploy it. It’s tempting to read posts about autonomous agents that goal-seek and think that you don’t need to make the boundary. You absolutely need to set a boundary for starting and ending.

There needs to be a clear trigger for starting the agent. This could be schedule-based (wake up every 2 hours) or event-based (when you get a webhook that a value changed in a record), and tells us to get started.

You need the same precision for when to stop. Is it a time limit or some other limiter that stops the agent from acting? And what happens if your agent is in an intermediate state and fails to complete its action?

Retry logic is important infrastructure. Your request might have failed because the resource is unavailable, or something else weird might have happened. It helps to know how many times you’ll attmempt the action before logging failure.

What happens if this agent runs twice?

Allowing the agent to rum more than once opens up the possibility that it might run successfully more than once. So what happens? If you’re thinking about this ahead of time, you’re designing for idempotency. That’s a fancy word meaning if you run a task more than once, you get a consistent outcome.

In practice, this means building in a condition (a switch, a flag, whatever you want to call it) that gets set when you run the Agent the first time. When you run that Agent again for the same record, the outcome will be ... nothing. So idempotency protects you from making changes due to race conditions or subsequent re-runs.

Make repeat runs of an agent boring, not dangerous, because your system knows what “done” looks like.

There’s one more test you can run to confirm that your agent will take the right action given real data. That entails creating a mode where the agent does its normal job, then logs what it would do instead of completing the action.

Building a “safe mode” is a great way to find the edge cases in your environment using real data. At that point, you can simulate the outcomes using real data and find the errors faster.

How do we keep this from getting expensive, or drifting into incorrect answers?

There’s one more wrinkle to consider. Because you’re likely using finite resources with your agents, it’s important to know the cost of an agent run.

Your costs are likely either token usage (for LLM calls) or finite resources like API calls. In either case you need to know the cost of running your Agent 10 or 100 or 1000 times. Then, put some guardrails in place to monitor the outputs.

If you’re using an LLM as part of your code, you need to check the outputs programatically. Instead of relying on “it seems off lately,” default to a data measurement in an Eval that you can test with a true/false or an LLM judge.

What evidence would tell us this agent is degrading?

Early indicators might include:

disagreement rates between humans and agent recommendations

changes in escalation frequency

confidence distribution drift

You don’t need to know how to build agents to lead teams building them. You need to know which questions prevent silent failure.

What’s the takeaway? As an ops leader, ensuring your agents get it right requires upfront testing and consideration. You wouldn’t launch a human process without testing, so make sure you do the same with agents.

Links for Reading and Sharing

These are links that caught my 👀

1/ The state of LLMs in 2026 - Andrej Karpathy has encyclopedic knowledge about how LLMs and chatbots function, so when he writes his year-end “what happened”, you should pay attention. Two things that stood out about this quote: “LLMs are emerging as a new kind of intelligence, simultaneously a lot smarter than I expected and a lot dumber than I expected.” First, we’re underestimating what these tools can do. Second, a whole new set of application layers is emerging.

2/ What visualizations did people use last year? - The team at Datawrapper shared a list of the most popular visualizations created by their users last year.

SPOILER: Tables and line charts are the winners!

3/ But before you build that line chart… - Check out this series of suggestions to make your line charts more effective. This is a great tutorial to give you specific steps (mostly removing info, adding specifics) for improving your visualizations.

What to do next

Hit reply if you’ve got links to share, data stories, or want to say hello.

The next big thing always starts out being dismissed as a “toy.” - Chris Dixon