This post was not written by an AI

"Everything Starts Out Looking Like a Toy" #117

Hi, I’m Greg 👋! I write essays on product development. Some key topics for me are system “handshakes”, the expectations for workflow, and the jobs we expect data to do. This all started when I tried to define What is Data Operations?

This week’s toy: an endless driving game in your web browser that generates landscapes and lets you experience the thrill of the open road. This one reminds me of classic video games because it doesn’t have much in-game logic. You just drive a car and the landscape changes. It’s oddly awesome. Edition 117 of this newsletter is here - it’s October 31, 2022.

The Big Idea

A short long-form essay about data things

⚙️ This post was not written by an AI

Creative work generated by artificial intelligence is having its moment. From DALL-E 2 – which builds highly detailed and trained images from almost any prompt, even when the prompts are outlandish – to writing tools like Jasper that create original writing content based on small inputs, AI content creation is here to stay.

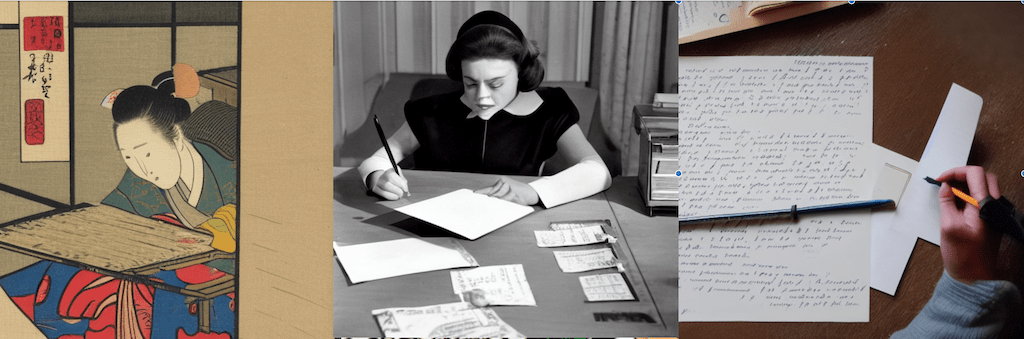

If you look at the example above, the model generates different images based on the prompt. The first one uses “A person writing a letter, Japanese woodcut” to filter the model; the next is based on a 1960s tv show, and the third one is a bit more free-form (what does writing a letter on Twitter mean, anyway?). At a glance, these images are pretty good. I don’t pretend to know how AI models like this work - suffice it to say you train it by letting it look at lots of photos. Then, the model can calculate the similarity between your prompt and the images it has indexed. At the end, write some prompts and get some images!

Why should you avoid using AI to create images?

AI models raise a few ethical questions for content creators. This computer code is building new images based on information scanned from the internet and is not paying any of those authors that trained it. Without this training data, it wouldn’t know anything.

Does this mean it’s not capital A “Art”? That’s a question for philosophers. Art is made by artists (and by people who make art) and there are undoubtedly questions if computer intelligence can be truly generative. But this AI generation is not going away. It might make very small adjustments without your knowledge (this happens inside your iPhone when you “take a picture”, or it might create entirely new options for you to choose from.

There’s a catch. Simply saying “I’m not going to use AI” may not be possible unless you go back to a film camera. It’s going to be really hard to avoid in the future. So we need to mitigate the problems this sort of technology can and will create. That includes figuring out how to signal when AI is being used and how to license this information for fair use.

You are going to be using AI to create images

There are a lot of good reasons to use an AI helper for knowledge work (yes, photos are just the start of this change.) They focus on generating a set of ideas that a human can then edit.

Here are a few helpful ways to use AI image prompts:

as a “scratchpad” to iterate ideas

to generate a specific type of image for a presentation or a prompt

produce almost limitless iterations of similar content

Ai models build, well, anything. They also help skilled operators produce work in a fraction of the time they did before. AI is going to cause changes for almost any knowledge work business because it produces “good enough” work very quickly with a low barrier to entry. (Here’s an example of companies working on this problem, curated by Elaine Zelby.)

It will be difficult to create a “moat” (a defensible advantage) by using only AI models as the lever. Knowledge work is going to evolve into something like prompt engineering where the best operators are the best “AI whisperers.” Because AI models start from human knowledge, we also need to be cautious and vigilant about declaring the bias inherent in these prompts.

The reward when we do this right? New business models. For example, Shutterstock is beginning to sell AI-generated stock images. This means they have realized that there is money to be made in generating this sort of image, and also that the software is not good enough to do it on demand. I believe that the software will be proficient at this task eventually and that there will remain an arbitrage between the work needed to make a “good” result and the work a prospect is willing to do.

Trying AI out: some practical examples

A simple example will help illustrate some of the ways AI-generated image models are effective today, and where they have room to grow to approach a creative human editor.

Where does AI struggle today?

AI models do not reproduce logos or text well in the way that we expect. You would think these models could index font families, read text, and be able to generate new text in a readable format. Likewise, you expect an AI model to be able to search for brand logos in the same way we use Google Images to search for an example.

AI models fail at this task, producing “words” that don’t look like readable words and logos and brand images that look like strange photocopy overlays of the expected thing. Both of these tasks feel like things that could be improved quickly with dedicated or human-assisted operation.

What AI models do well

Models do well with generic prompts and a style (for example, “cat, japanese woodcut”). When you use an item with more examples on the Internet, the outcomes also seem better. This makes sense when you consider the importance of many overlapping instances of similar images for producing a decent outcome. copying the stylistic cues of many images on the internet, especially the more training images that exist.

To improve the likelihood of success, don’t ask the model to do too much, yet. There is a tendency to look at some of the amazing images this method can produce and think great results happen automatically.

An Example: portraying Spider-man’s J. Jonah Jameson

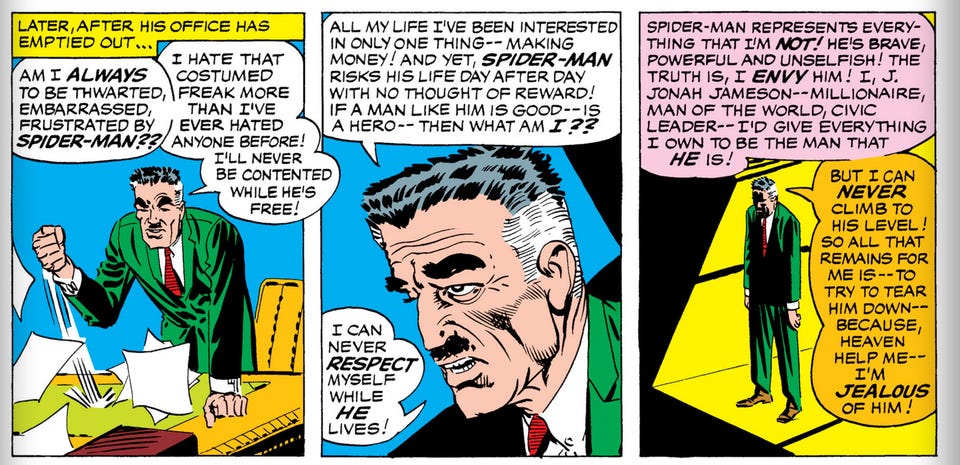

Let’s try it out with DiffusionBee, a desktop app using the AI model StableDiffusion. I asked this app to create a picture of J. Jonah Jameson, the newspaper publisher from the series of Spider-man comics. The goal was to recreate an image in the style of Steve Ditko and John Romita, comic book artists who drew Spiderman in the 1960s.

Here’s an example of panels from the actual comic books:

And here’s an example panel created by the AI model using a comic book prompt.

It’s got the right idea, rendering some comic panels, capturing Ditko’s signature style, and creating a character that looks reasonably like JJJ. (If you’re a Spider-man fan, I think this looks more like Norman Osborne, but I will give the AI a pass on this one.) The model fails miserably at creating copy for the comic bubbles.

Compare this example to the AI generating a portrait of J.Jonah Jameson as a cat.

Is it “believeable”? Part of the reason that our brains want to accept this as a believable outcome is that it looks like a portrait, follows the conventions of photography, and is relatively seamless as an outcome. You won’t get the same outcome twice, though. Also, the same prompts produce different results on different generative models.

A Proposal for AI Metadata

We need a way to identify how images are generated that is displayed and easily readable along with those images. There are many reasons for this, chief among them the need to compensate creators, limit copyright infringement, and present the option to filter images people don’t want to see because of their content or generation model.

A modest proposal here would be to adopt a standard like the one already in use for JPEG images. EXIF files are a standard for metadata documentation and help people determine the original image criteria. A version of this for AI-generated images might include the original prompt, the engine and version used to produce the image, and the URL of the seed that produced the image. While it’s hard to speculate on any changes that might happen with IP law and copyright for existing images, adding this data lineage would help allocate any money that acrues from selling these images. (Makes you wonder how Shutterstock and other providers are going to address this question.)

This post was not written by an AI. Why is that? The primary reason is that these models can’t reason like people yet. Will they ever get there? It comes down to better understanding when we encounter original thought. In the future almost everyone will use AI assistance for creative work. I’m confident that we’ll still be able to tell the difference, though we might require AI-detecting assistance to help us.

What’s the takeaway? AI generation for creative work is becoming more common, and is likely to provide at least one option in most creative software going forward. To respond, operators (and creators) need to learn the parameters that help AI to deliver the best results, and invent new ways to be unique.

Links for Reading and Sharing

These are links that caught my 👀

1/ Two pizza teams and meaningful work - When you’re working on a project and it’s going slowly, more resources sound like a great thing to have. But adding resources to a project don’t guarantee better success. This post brilliantly shares that the problem is often lack of clarity rather than lack of resource. Put another way, stopping to remember why we are doing something often yields better results than getting more help.

2/ Crafting output metrics to measure impact - John Cutler is so good at creating models for understanding activity, I want to read every post he writes twice.

Here’s an excellent example of a prompt to design the metrics for a project:

Right now we are working to improve the ______A________ ______B________ for ______C_______ which we could potentially measure by tracking _____D_______.

This superprompt helps you to exit the analytics design process with meaningful metrics that will make a difference for your business.

3/ Building Analytics Requirements - I really enjoyed Sarah Krasnik’s Analytics Requirements Document. This post describes the parallel process we need to do as builders when creating the analytics needed to measure our projects. Too often these steps are not included in a Products Requirement Document. Anohter, related item that needs to follow this initial analytics assessment: a metrics catalog for the organization. This details a definition, a label, an owner, and change history for each metric. (Bonus points if the lineage of one metric to another is diagrammed.)

What to do next

Hit reply if you’ve got links to share, data stories, or want to say hello.

Want more essays? Read on Data Operations or other writings at gregmeyer.com.

The next big thing always starts out being dismissed as a “toy.” - Chris Dixon