What do you build when you can build anything?

With AI, everyone can build quickly with fewer engineering resources. Does this reduce or increase problems? Read: "Everything Starts Out Looking Like a Toy" #288

Hi, I’m Greg 👋! I write weekly product essays, including system “handshakes”, the expectations for workflow, and the jobs to be done for data. What is Data Operations? was the first post in the series.

This week’s toy: A microcontroller that runs code to display the next bus arriving nearby. Perhaps the next revolution of AI will be a breakthrough in physical 3d printing to enable us to build software+things. Want to build a switch for your desk to change the song or a toggle to start the dishwasher? (Or perhaps more practical things.)

Edition 288 of this newsletter is here - it’s January 19, 2026.

Thanks for reading! Let me know if there’s a topic you’d like me to cover.

The Big Idea

A short long-form essay about data things

⚙️ What do you build when you can build anything?

The most dangerous outcome of unlimited building capacity is that you can become very good at fixing symptoms without eliminating the root cause. The bottleneck moved from technical risk to judgment. You need to know when a fix teaches you something and when you are “kicking the can” and papering over a deeper flaw.

Before 2024, effectiveness was constrained by tooling. Even if you knew what you wanted to change, you had to determine how to get it done cheaply, safely, or quickly to earn a release. Scarcity of engineering resources forced prioritization. It also hid some bad judgment because you couldn’t just ask Claude “how do I fix that?”

That engineering constraint is gone, thanks to Agents and LLMs.

It’s possible to build tools, scripts, workflows, dashboards, and automations faster than organizations want or can even run a decision process to decide whether it’s a good idea. The result is uneven effectiveness. Some teams compound their gains, and others get very busy fixing the same problems faster.

The difference might be the question: “is this the right fix to solve the problem, every time it happens?”

The dashboard that didn’t deflect anything

Let’s take a familiar example. When support volume is rising, everyone agrees it’s a problem. So you build a dashboard that shows volume by category, deflection rate over time, and the top repeated questions.

Everyone loves the dashboard, and it initially focuses the team on solving some of the most important problems faced by customers. Hooray for progress!

Now fast forward to several weeks later, when support volume hasn’t meaningfully changed. The team has identified exactly where the problem is happening. But it’s still happening.

Trying to harden the system

The dashboard did its job: it surfaced the problem. The response is where things go wrong. The support dashboard exposes problems in the data. Perhaps category data is not normalized. Maybe there’s a double counting problem. It could be a legitimate schema change that wasn’t shared with the operational team.

So engineers respond rationally by normalizing data, introducing helper libraries for categorization, and other abstractions. They also ask AI for a good fix, and it’s great at this!

Each of these decisions is defensible. When they’re not aligned, they quietly raise the cost of change.

Now the dashboard works better, but contains a new library that no one has used before. Fewer engineers understand the pipeline end to end. Small changes take longer because the codebase has some new pathways. And the original problem remains: customers still ask the same questions.

The issue isn’t complexity itself. It’s structure introduced before the system has earned it. Those abstractions harden assumptions that haven’t been tested yet. And AI is a very good multiplier for this problem. In the hands of someone who’s not sure how to improve things, AI will attempt to complete the answer.

Teams that use AI and exhibit some caution when using it gain the benefits of fast iteration plus engineering discipline.

As an engineer, you want known systems:

Favor primitives over patterns

Boring code you can reason about six months later

As little abstraction as possible

These simple solutions may take longer to build than a quick fix. Many teams fix symptoms because incentives quietly reward it. System-level fixes are slower, harder to attribute, and often invisible when they work. Over time, organizations train people to optimize for visible artifacts instead of reduced work.

PMs want to use bugs for learning, but might get optimistic

PMs approach the same situation and run into a different local maximum.

They look at the dashboard and see the top repeated questions. They respond rationally:

Writing help center articles

Adding tooltips

Creating canned responses

Occasionally fixing small bugs themselves

These fixes don’t solve the root cause of the problem and make the paper cuts less painful instead. The goal should be strategic, well-chosen small fixes. These are the kind that eliminate the cause.

Bug-fixing can be one of those mommnts when it’s used as discovery. For PMs, fixing a bug teaches things no roadmap ever will:

Where assumptions break

Which defaults confuse customers

How data actually flows

Why “simple requests” aren’t simple

But caution: If PMs fix symptoms without eliminating the cause, they become a patch layer. Instead, we want a reinforcing loop:

Fix → learn → redesign the system so the fix is no longer needed

Otherwise, we’ve fixed the symptom and not the problem.

Immediate relief vs long-term leverage

This argument assumes basic hygiene exists: ownership is clear, failures are observable, and changes can be shipped safely. If those foundations are missing, symptom-fixing isn’t a mistake, and is often the only way to regain control.

The danger starts once hygiene is in place and teams keep treating recurring problems as one-off fixes. Not all fixes are bad, and not all leverage is good.

Sometimes immediate relief is correct:

A customer-visible issue

A frequent, expensive failure

A fix that is clearly bounded and reversible

Sometimes long-term leverage is required:

When the same class of problem keeps reappearing

When ownership or decision rights are unclear

When every change requires explanation and coordination

Teams get into trouble when they confuse the two:

Building “platforms” when customers need relief

Shipping patches when the system needs redesign

The test is simple:

Does this reduce future friction, or just reduce noise today?

Speed is not the metric. Direction is.

Designing systems that can change

When capability is abundant, the goal is no longer to build correct systems. It’s to build systems that can change safely.

Effective systems:

Favor incremental delivery over big rewrites

Replace questions with defaults

Make status observable instead of reported

Encode judgment once, not repeatedly

Fail in ways that are visible and recoverable

This is where engineers and PMs converge. Both are now constraint designers, and changeability is the real form of leverage.

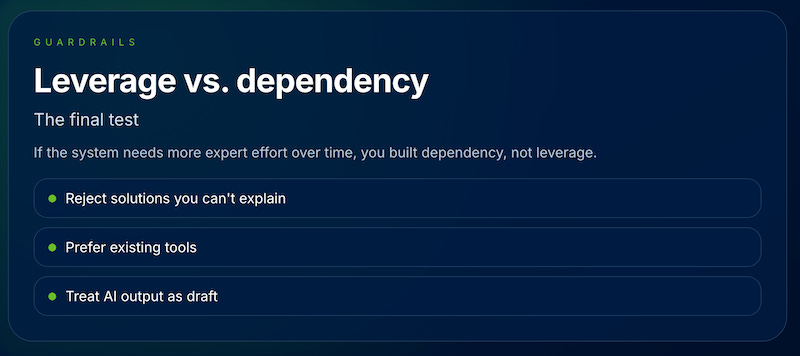

Guardrails against fixing symptoms forever

Abundance – especially AI-assisted abundance – introduces entropy by default. Discipline matters more than ambition.

A few rules that scale:

Reject solutions you can’t explain to a teammate

Prefer existing tools over novel ones

Treat AI output as a draft, not a decision

Be suspicious of fixes that feel “too clean”

Clever systems age poorly. Boring systems evolve.

The final test of effectiveness isn’t how fast you ship, how much you automate, or how elegant the solution looks.

If your system requires increasingly skilled people to keep it running, you didn’t build leverage; you built a dependency.

What’s the takeaway? Building is abundant; judgment is scarce. When you make changes, ask: does this reduce future friction, or just noise today? Your goal should be building systems to change safely, not ones that require experts to always be on call.

Links for Reading and Sharing

These are links that caught my 👀

1/ “Ok, computer” - The next leap in creating software will probably start from a phone with a voice conversation. Agents doing the work remove the need for you to be in front of a keyboard, so what will be different? (And what need challenges and opportunities will arise?)

2/ How do you trust an agent? - For agents that deal with money, you define a set of rules for fiduciary responsibility. Next, an observability layer that helps consumers to know if the agents actually did what they were supposed to do (think star ratings for mutual funds conducted by an independent agency for a model here.) Yep. it’s early days.

3/ What does a skilled operator do now? - if you believe (like I do) that AI is a useful set of tools and that as skilled operators, we need to learn how to use them, what do you do if you’re feeling behind? The short answer: get started using the tools, and don’t worry if you’re doing it it right. AI may not take over your job, but you’ll be a lot better at your job if you can articulate how you can make it better (or not) using AI.

What to do next

Hit reply if you’ve got links to share, data stories, or want to say hello.

The next big thing always starts out being dismissed as a “toy.” - Chris Dixon